Most gardeners hear “bindweed” and immediately reach for the shovel, vinegar spray, or worst-case-scenario herbicides. I don’t blame them, bindweed has earned its reputation as one of the most stubborn, invasive plants in temperate gardens. Its roots can stretch meters deep. It strangles tender seedlings. And if you so much as blink, it feels like it’s covered half your fence.

But what if I told you there’s another side to bindweed? As a lifelong gardener and ecological soil manager, I’ve spent years trying to understand not just how to get rid of certain plants, but why they appear in the first place. Bindweed is one of those “why” plants. The more I paid attention, the more I realized this so-called pest was doing something intelligent, even helpful. Below are five reasons bindweed might not be the enemy we think it is, and how, with careful management, it can actually benefit your garden.

1. Bindweed Breaks and Remediates Compacted Soil

One of bindweed’s most overlooked traits is its ability to drive deep into hard, compacted soil. Its root system is no joke, it’s designed for survival. But from a soil health perspective, that’s exactly what makes it so useful. In areas where even daikon radishes struggle, bindweed’s taproots can bust through layers of clay and hardpan, naturally aerating the earth. That’s free labor most of us miss because we’re too busy pulling it out.

What’s more, bindweed doesn’t just punch holes in the soil. It pulls up minerals from deeper layers, especially calcium and magnesium, making them more available to shallow-rooted plants when its foliage dies back or is composted. That kind of mineral cycling is a core principle in regenerative agriculture. Most people pay money for cover crops to do that job, bindweed is doing it uninvited.

I’ve seen neglected parts of my garden, where the soil was dense, lifeless, and compact, slowly shift back toward health after bindweed had a chance to grow there for a season. I didn’t plant anything else. I just observed. A year later, the soil had improved texture, better drainage, and was teeming with earthworms. Bindweed had done the heavy lifting.

2. It Functions as a Living Mulch

Weeds often outcompete garden plants because they know how to cover ground quickly. Bindweed, with its creeping vines and overlapping leaves, is an aggressive ground cover. But that’s also what makes it effective as a temporary living mulch. I’ve used it, believe it or not, to suppress other, more disruptive weeds like Bermuda grass and chickweed, which are harder to manage and offer no soil benefits in return.

Bindweed keeps the soil cool and moist during hot months and prevents erosion in bare beds. If you’ve ever pulled it up after a rain, you’ll notice the soil underneath stays dark and loamy, not dried out or baked like exposed beds. In struggling zones where I wasn’t ready to plant crops yet, I’ve let bindweed run as a natural blanket to hold space.

Of course, timing and control are everything. You don’t let it take over your tomatoes. But in unplanted areas, or edges of your property, bindweed can act like a natural placeholder, reducing compaction, locking in moisture, and denying space to more aggressive invaders. When I’m ready to plant in those areas, I cut the bindweed at the base and cover it with a thick mulch layer. It dies back without a fight, and I get the benefits of the organic matter it left behind.

3. It Attracts Pollinators You Didn’t Know You Needed

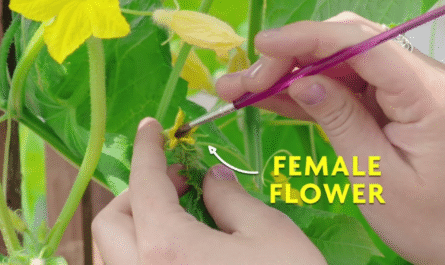

Bindweed flowers are often dismissed as pretty but pointless. In fact, they’re nectar-rich and bloom over long periods, making them a reliable food source for pollinators when other plants aren’t producing. I’ve watched bees, hoverflies, and even hummingbirds spend time on bindweed blooms, especially in the early morning when little else is available.

In a garden designed for biodiversity, every nectar source counts. Sometimes the most surprising plants are the ones keeping your ecosystem functional behind the scenes. During dry seasons when traditional flowers wilt, bindweed keeps blooming. That consistency supports pollinator populations that then move on to your cucumbers, squash, and melons.

I ran an informal experiment two summers ago by allowing bindweed to grow along a fence that bordered one of my underperforming vegetable beds. Within weeks, pollinator visits doubled.

The squash in that bed, which had barely been fruiting, suddenly took off. It wasn’t magic, it was bindweed providing the bait to bring the pollinators in. The bonus? I didn’t have to seed a new flower patch or buy wildflower mixes to achieve the effect.

4. It Creates Shelter for Beneficial Insects and Small Wildlife

If you’ve ever looked closely at a bindweed tangle, you’ve probably seen spiders, ladybugs, and even small frogs tucked into the vines. Bindweed creates microhabitats, shady, safe spots for critters that keep your garden in balance. While we often think of “pest control” as something that comes in a bottle, real ecological control starts with encouraging natural predators to stick around.

Insects like lacewings and parasitic wasps need shelter to breed and overwinter. Bindweed provides that. Frogs and toads, which can consume thousands of insect pests in a season, are more likely to inhabit gardens with dense low cover. By ignoring bindweed in certain marginal zones, especially against walls, under trees, or in corners, I’ve seen an uptick in exactly the kinds of creatures I want living in my yard.

There’s a reason monocultures fail, they lack structure. Bindweed adds a level of messiness that, when managed thoughtfully, introduces complexity to your garden. And complexity brings balance. You won’t see that result in a week or even a month. But over a growing season, bindweed can quietly invite the right players into your garden drama.

5. It’s a Living Indicator of Soil Conditions

Bindweed doesn’t show up randomly. It’s what we call a “soil indicator plant,” its presence reveals specific soil conditions, particularly compaction, nutrient imbalance, or poor organic matter. If bindweed is thriving somewhere in your yard, it’s telling you something other plants can’t. It grows where the soil is tight but mineral-rich, where competition is low, and often where water stress is high.

Instead of ripping it out right away, I’ve learned to observe it. Where does it cluster? Where does it struggle? How does it respond to changes I make, like composting or aerating? I now use bindweed as part of my garden diagnostics. It’s not as flashy as a soil test, but it’s faster and always available.

This insight has helped me spot trouble before it shows up in my crops. One year, I noticed bindweed starting to cluster around my asparagus bed. I did a quick inspection and found early signs of compaction. I aerated lightly, mulched heavily, and watched the bindweed fade back on its own. Problem solved, without pesticides, without stress. Bindweed was the warning light. I just had to know how to read it.

Final Thought

Bindweed doesn’t have to be your nemesis. It can be a tool, a signal, even a silent partner in restoring garden health, if you approach it with curiosity instead of fear. I’m not saying let it take over.

But when you start asking why it’s growing instead of just how to kill it, you unlock a deeper understanding of your garden’s hidden systems. Sometimes the weeds know more than we do.

FAQs

Only if you let it grow unchecked. Strategic use, like in unused beds or boundary zones, can offer benefits without competition. Bindweed doesn’t have to invade if you give it a job and boundaries. Absolutely. The key is control. Cut it back before flowering or seed set, and use it in areas where you're not actively cultivating food crops. Think of it like a wild cover crop with a leash. Yes. Regular cutting, shading, and covering with mulch suppress its growth over time without destroying its root system completely. You can guide its behavior without scorched-earth tactics. Definitely, plants like dandelion, chicory, and plantain also act as soil indicators, pollinator plants, and natural aerators. Bindweed just happens to be one of the most aggressive and most misunderstood. Will encouraging bindweed hurt my vegetables or flowers?

Can I use bindweed without letting it take over everything?

Is there a way to control bindweed without killing it completely?

Are there other “weeds” that behave like bindweed in helpful ways?