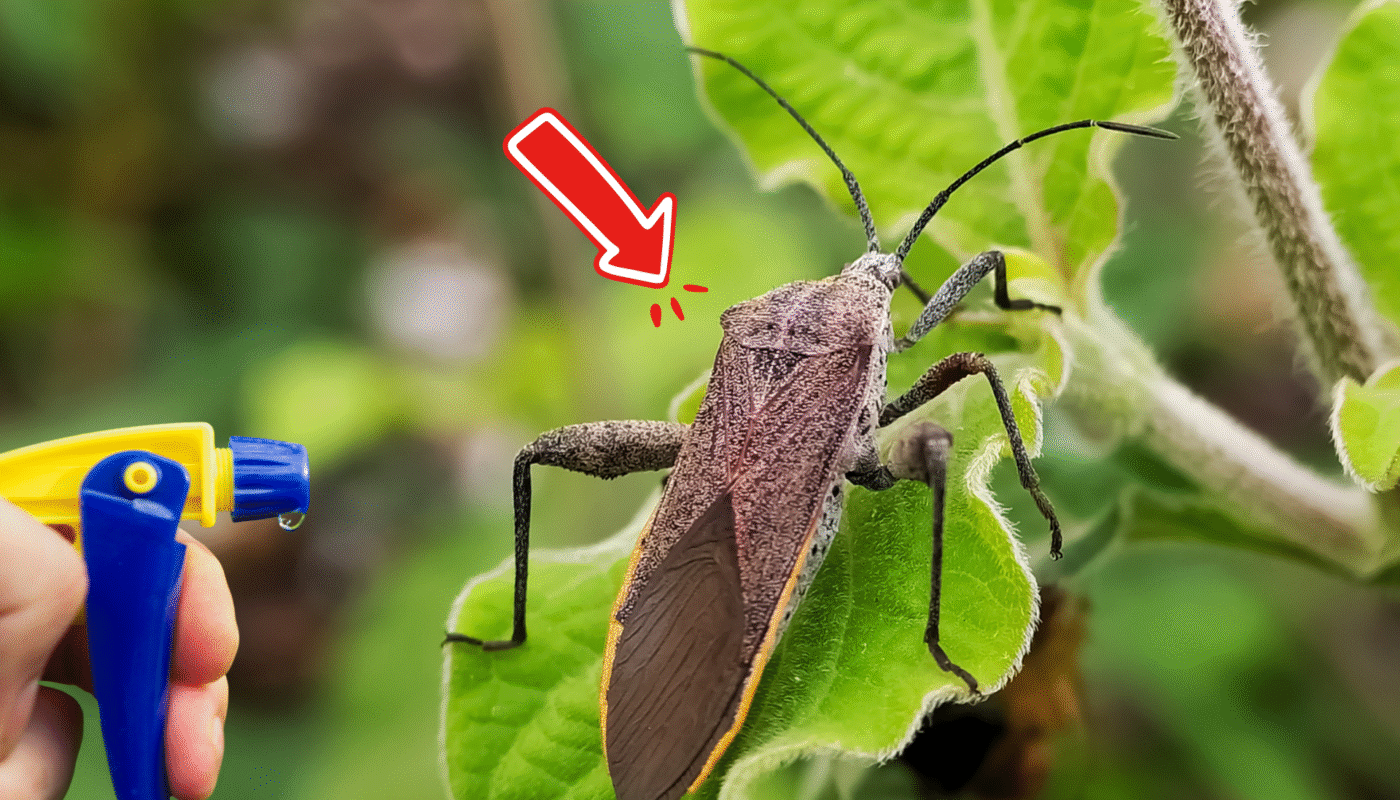

Every year, squash bugs try to stage a takeover in my garden. And every year, I make sure they lose. Over time, I’ve learned that beating squash bugs isn’t about spraying them into submission or relying on quick fixes. It’s about building a system that makes your garden unwelcoming to them, season after season.

If you’re serious about growing healthy squash, pumpkins, or melons without these pests wrecking your harvest, it takes a multi-layered approach rooted in timing, cleanliness, strategy, and vigilance. Let me walk you through exactly how I do it, and how you can too.

How Squash Bugs Operate

Before you can beat squash bugs, you need to understand how they live. These pests overwinter in debris, old leaves, stems, woodpiles, and even mulch. Come spring, when temperatures rise, they emerge ready to feed, mate, and lay clusters of coppery eggs on the undersides of squash leaves. They’re sneaky. At first, you’ll see a few wilting leaves and might blame it on watering. But soon, entire plants collapse under the stress of repeated feeding.

They prefer squash, particularly zucchini, but I’ve seen them go after pumpkins and melons with equal aggression. The adults are flat, brownish-gray, and shaped like stink bugs. But it’s their lifecycle that makes them hard to kill.

The nymphs hatch and start feeding immediately, but it’s the adults that are most resilient, and the ones that will return next year if you don’t take action. Killing the bugs you see is just scratching the surface. You have to disrupt their entire cycle.

I’ve adopted a year-round strategy to permanently drive squash bugs out of my garden. It’s not just one solution; it’s an ecosystem of choices that make survival nearly impossible for them. Let’s break that down, step by step.

The Crucial Winter Clean-Up

It starts long before planting season. I always do a deep garden clean-up in the fall, not just for aesthetics or disease prevention, but specifically to target overwintering squash bugs. I rake up every dead leaf, pull old vines, and even check under tarps or garden tools where bugs might hide. If it’s a material they can’t tuck into for the winter, I remove it or relocate it far from where I’ll plant squash.

The key is consistency. Squash bugs are creatures of habit. They return to the same hiding spots year after year. When I eliminate those safe havens, I drastically reduce the spring emergence. That said, I don’t strip my entire garden bare. Organic matter is still valuable for the soil. So I balance this by leaving some debris in beds where I don’t plan to grow cucurbits. That way, beneficial insects still have a place to shelter without giving the squash bugs a free ride back into my patch.

Composting plays a role here, too. If I toss infested vines into my compost pile, I’m basically providing a resort for squash bugs. I burn or seal away any squash vines or plant parts that show signs of infestation. That’s non-negotiable. I treat clean-up like pest control, not just maintenance.

Also Read: 9 Natural Ways to Keep Pests Out of Your Vegetable Garden for Good

Crop Rotation That Actually Works

One of the most underused strategies I see among gardeners is meaningful crop rotation. Simply moving your squash to the next bed over isn’t enough. Squash bugs can crawl, fly short distances, and they have a strong memory for location. I move my squash at least 20 to 30 feet each year, and if I can, I rotate them to the opposite end of the garden.

But I don’t just rotate randomly. I track my planting locations using a simple garden journal. I note what went where and when, and I map out rotations a year in advance. If I planted squash in the north bed this year, I won’t put it back there for at least two more seasons. This prevents a buildup of not just squash bugs, but also squash vine borers and soil-based diseases like powdery mildew.

If space is limited, I’ve even grown squash in large containers for a season and placed them in a completely different part of my yard. Rotation is about disrupting expectations. Squash bugs wake up and go to the same spot. When the buffet isn’t there, they either move on or die off. That’s the goal.

Smart Use of Row Covers

I use floating row covers in early spring, not just for frost protection, but to physically block bugs from laying eggs. Timing is everything. I install row covers on the day I plant my squash. It’s not just about exclusion; it’s about buying time. Every day I delay the first egg-laying cycle, the better my chances of outrunning the population curve.

Once the plants start flowering, I remove the covers. Pollinators need access, and leaving covers on for too long stunts fruit development. But by then, if I’ve done my early cleanup and rotated effectively, there are fewer adults around to lay eggs. If I see any signs of infestation during this phase, I’ll do evening patrols and manually remove bugs and eggs, more on that later.

One tip: I anchor the covers tightly with bricks or landscape staples. Squash bugs are persistent. They’ll crawl under any loose edge. And I make sure the covers are well-ventilated. Trapping heat or moisture can invite fungal problems. The covers are a defensive tool, not a set-and-forget fix.

Rethinking Mulch

Mulch is a double-edged sword when it comes to pest management. At first, I used wood chips or bark mulch around my squash, but I noticed more bug activity, especially on hot, humid days. They love dense, moist environments. Now, I’ve switched to straw mulch, and I’ve seen a significant drop in infestations.

Straw is lighter, drier, and less inviting to squash bugs. It still suppresses weeds and conserves soil moisture, but without creating the cozy hiding spots the bugs prefer. The downside? It breaks down faster and sometimes harbors weed seeds. I compensate by applying it in thinner layers and replacing it mid-season if it starts to mat down.

I also use mulch strategically. I keep a mulch-free perimeter around the base of each plant, about 3 to 4 inches. This exposes the soil surface and makes it harder for bugs to travel undetected to the stems. It’s a subtle tweak, but it’s made my hand inspections much easier.

Try Companion Plants

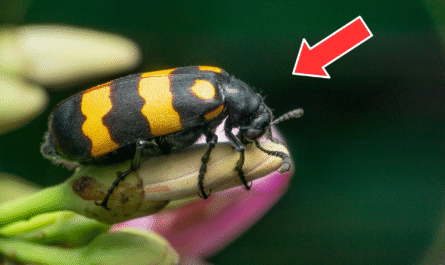

I always plant marigolds, nasturtiums, and calendula around my squash beds. Not only do they attract pollinators, but their strong scent seems to confuse or deter squash bugs. I don’t rely on companion planting alone; it’s not a silver bullet, but it adds another layer of resistance.

I’ve also experimented with trap cropping. For example, I’ll plant blue hubbard squash a few feet away from my main zucchini bed. Squash bugs are more drawn to blue hubbard than most other varieties. Once they congregate there, I destroy the trap crop along with the bugs. It’s brutal but effective.

Another trick? Letting dill and oregano flower near my squash. These herbs attract beneficial insects like parasitic wasps and tachinid flies, which prey on squash bug nymphs. Creating a supportive ecosystem isn’t about avoiding nature, it’s about turning nature to your advantage.

Vigilant Manual Control

No matter how many preventive steps I take, I still scout my plants every 2–3 days during peak season. I check the undersides of leaves for eggs, tiny bronze ovals in neat rows, and scrape them off with duct tape or a plastic knife. I drop adults and nymphs into a bucket of soapy water. It’s not glamorous, but it works.

I time my hand-picking for early morning or dusk, when bugs are less active and easier to catch. This is also when plants are least stressed, so I’m not interrupting their photosynthesis. During high-infestation years, I’ll even designate one sacrificial plant just to collect bugs, then pull and dispose of it mid-season.

This process, while tedious, gives me a real-time sense of how effective my other strategies are. If I’m seeing fewer eggs and nymphs each week, I know my ecosystem is working. But I never let my guard down. One unchecked cluster of eggs can explode into a full infestation in days.

Final Thought

I’ve tried every spray, dust, and DIY mixture under the sun. None of them work long-term. Squash bugs are too tough. Their eggs are resistant, their adults are armored, and their hiding spots are endless. The only thing that works permanently is building a garden system that doesn’t welcome them.

So my approach is holistic, seasonal, and relentless. I don’t let up in winter, I don’t plant blindly, and I don’t ignore the early signs. I combine physical barriers, crop rotation, smart plant partnerships, and old-school vigilance. Year by year, I’ve watched squash bugs dwindle until they’re a minor nuisance, not a garden killer.

If you’re ready to stop reacting and start controlling, take this system seriously. It’s not about doing one or two things, it’s about doing all of them well, all the time. That’s how you kick squash bugs out for good.

FAQs

Early morning and late evening are ideal. That’s when squash bugs are slower and more likely to be found on the undersides of leaves. Avoid midday checks when they hide in the soil or stems, making them harder to spot. I recommend at least 20 to 30 feet away from the previous year’s location. If space is limited, consider growing in containers or vertical setups on decks or patios to break the pest cycle. Yes, especially ducks. They forage low and love eating soft-bodied nymphs. I let my flock into the garden in the off-season or early spring before planting. Just be cautious, during the growing season, they can damage young plants. Yes, some varieties like butternut and delicata squash tend to suffer less damage than zucchinis or summer squash. They have tougher vines and less appealing foliage. But even these varieties need protection in heavily infested areas. What’s the best time of day to scout for squash bugs?

How far should I rotate my squash plants each year?

Can chickens or ducks help with squash bug control?

Are there any squash varieties more resistant to squash bugs?