Across the open pastures and feedlots of the American heartland, a silent but menacing threat is creeping back toward U.S. livestock: the New World screwworm (NWS).

Although largely eradicated decades ago, recent reports from Oaxaca and Veracruz, nearly 700 miles south of the U.S.-Mexico border, have raised alarms: the fly is once again advancing northward, threatening to ignite economic and animal health crises reminiscent of a darker chapter in agricultural history.

What Exactly Is the New World Screwworm?

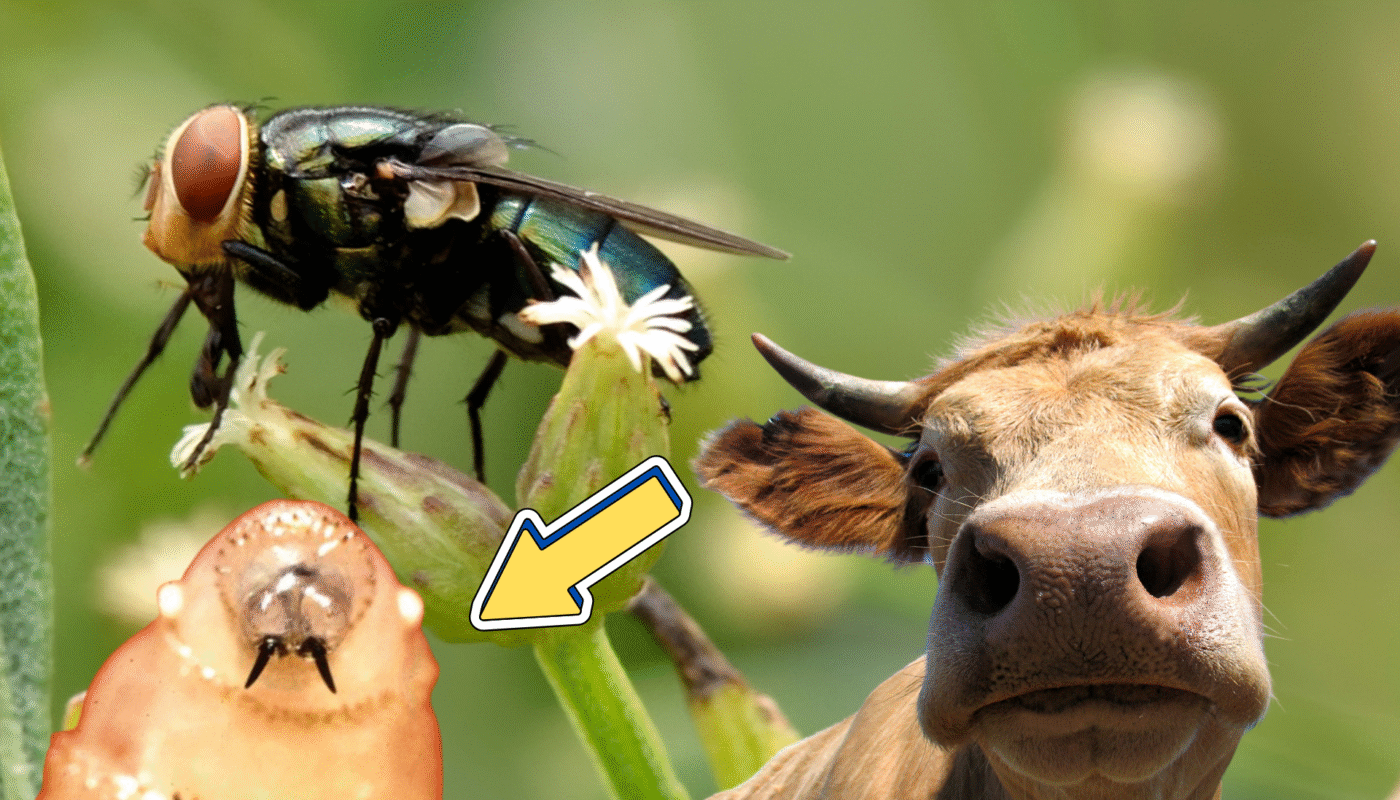

At first glance, these flies might seem harmless, roughly housefly-sized, with metallic green or blue bodies and distinctive orange eyes. But it is their offspring, not the adults, that inflict devastation.

The larvae are fleshy, tapered maggots equipped with tiny, forward-facing bands of spines and rasping mandibles. Latching onto any livestock wound, no matter how small, they burrow into tissue, devour flesh, and leave behind deep, festering lesions.

In severe infestations, wounds may teem with hundreds of maggots, causing excruciating pain, severe weight loss, or even death, especially in neglected or immune-compromised animals.

A broad-spectrum menace, NWS can infest not just cattle, but sheep, pigs, horses, wildlife, birds, pets, and even humans (though rare). Classic warning signs: animals that eat less, shake or toss their heads repeatedly, emit foul odors, or show rapidly expanding sores with visible maggots. Spotting such symptoms should trigger immediate action: call your veterinarian, alert your state animal-health agency, and report to APHIS without delay.

Historical Battle

The United States first felt the full force of the screwworm menace in the 1930s, when livestock losses began to mount. By the 1950s, scientists discovered that sterilizing male flies through radiation, a process that left them alive but unable to impregnate females, was a game-changer.

The females mate once in their lives, so releasing countless sterile males into the wild drastically cuts reproduction. This “Sterile Insect Technique” (SIT) became a scientific hero.

Between 1966 and 2006, the U.S. successfully eradicated screwworms from the mainland. Mexico followed suit by 1986. Meanwhile, Panama and the U.S. maintained a resilient barrier zone, regularly releasing sterile insects to block reinvasion. The 2016 detection in the Florida Keys was swiftly handled through these established SIT protocols.

But eradication warps only so far as vigilant commitment. Since 2023, Panama has reported unusually high screwworm levels, hinting at larger vulnerabilities in the sterile-release chain.

A Timeline of Escalating Threats

Here’s a chronological recap, underscoring the accelerating nature of this crisis:

- May 29, 2025: The USDA commits $21 million to refurbish a fruit-fly production plant in Mexico. The upgrade aims to generate an additional 60–100 million sterile screwworms weekly.

- May 22, 2025: The American Farm Bureau warns screwworm numbers have surpassed containment thresholds.

- May 15, 2025: The U.S. Senate introduces the “STOP Screwworms Act,” signaling legislative urgency.

- May 11, 2025: APHIS confirms live screwworms are just 700 miles from the border. They impose a temporary 30-day hold on all live cattle, bison, and horse imports from southern neighbors.

- February 25, 2025: USDA redirects sterile-fly releases deeper into Mexican territory.

- February 1, 2025: U.S. and Mexican agencies formalize joint inspection and treatment protocols; animal trade resumes.

- December 16, 2024: APHIS earmarks $165 million for emergency screwworm control in Mexico and Central America.

- November 22, 2024: Detection of screwworms in Mexico prompts a shutdown of live-animal imports.

- 2023: APHIS notes record-high screwworm activity in Panama.

- 2016: Swift SIT intervention eradicates Florida Keys outbreak.

- 2006: U.S.–Panama screwworm barrier zone becomes operational.

- 1986, 1966: Mexico and the U.S. complete widespread eradication.

- 1950s: Researchers pioneer the sterilization technique.

- 1930s: Screwworms emerge as a major livestock threat.

The escalating string of events, especially in 2024 and 2025, showcases both the panic and action when a frontier pest draws dangerously close.

larvae of the New World Screwworm

The Stakes: Millions at Risk

No small bother, screwworm infestations inflict tangible, large-scale economic losses. In the 20th century alone, creeping infestations cost U.S. livestock producers over $100 million annually. APHIS predicts that an unchecked resurgence could once again wipe out millions in production losses.

The consequences ripple far beyond individual ranchers: meat prices surge as producers struggle to replace lost animals and invest in treatment. Trade embargoes slam down across borders, rerouting livestock supply chains and chilling international commerce. Then there’s the unseen toll, animal suffering, ecosystem imbalance, and the reputational costs of widespread disease outbreaks.

APHIS Secretary Brooke Rollins put it in no uncertain terms: “The last time this devastating pest invaded America, it took 30 years for our cattle industry to recover. This cannot happen again.” That blunt warning underscores how slowly and expensively screwworms can grip, then subside.

How SIT Works—and Why It Matters

The sterile insect technique hinges on a simple yet powerful biological principle. Male screwworms are mass-irradiated to render them infertile. When released into the wild, they compete with fertile males. Once mated, the female lays eggs that fail to hatch. Since she mates only once, that female’s entire reproductive potential is nullified.

The challenge: consistent mass production and precise, regular aerial release, 44 flights per week currently, are essential. The Panama–U.S. Commission for Eradication and Prevention of Screwworm (COPEG) leads this battle from its Eastern Panama production facility.

The USDA notes current operations are running at maximum capacity, releasing roughly 100 million sterile flies weekly. There is no slack in the system; if demand rises, existing production cannot scale overnight. That’s why the new $21 million upgrade in Mexico is critical: to increase production by 60–100 million sterile flies weekly.

Beyond SIT: Science, Surveillance & Regulation

While SIT is the lynchpin, a robust defense strategy demands more:

1. Early Detection & Rapid Response

Consistent surveillance for livestock sores and unusual symptoms is imperative. Rapid testing and quarantine protocols help inhibit outbreaks before they spread.

2. International Collaboration

The U.S. and Mexico now share inspection, treatment protocols, and data. Periodic trade suspensions ensure safety when risks spike, a proactive reassurance to domestic producers.

3. Research Innovation

Scientists are exploring advanced genetic tools, beyond simple sterilization, such as gene drives that could suppress ancestral screwworm populations or make them sterile in the wild.

4. Legislative Backing

Legislation like the STOP Screwworms Act funds infrastructure, research collaborations, and emergency-response readiness from federal, state, and international agencies.

5. Farmer Education

Producers must be trained to spot early signs, report quickly, and safely manage infected animals, especially in shared border regions and remote ranchlands.

Economic Ripple Effects

Let’s dig deeper into how screwworm outbreaks ripple through the economy:

- Direct Production Losses

Animals that lose weight, become injured, or die due to screwworm infestations result in production delays or total losses. The 20th-century cost estimates of $100 million annually reflect these direct losses alone. - Rising Input Costs

Increased vet services, quarantine measures, specialized treatments, and improved fencing/all-weather cover all carry costs. - Meat Supply Shock

As afflicted herds are culled and production contracts, meat scarcity temporarily bumps prices for supermarkets and restaurants. - Trade & Export Disruptions

International buyers, concerned about disease ingress, may tighten import standards or halt purchases; export bans can decimate already-lean profit margins. - Insurance Claims & Premium Hikes

Livestock insurers face high payouts; in response, they increase insurance rates or tighten coverage conditions, forcing producers to self-insure or exit smaller players from the market.

Why Now, and Why It’s Getting Harder

Several forces have made safeguarding against screwworm more challenging in recent years:

1. Climate Change

Warming temperatures and shifting rain patterns have extended screwworm breeding seasons and expanded suitable habitat further north.

2. Funding Fatigue

As screwworms remained off the mainland for decades, some stakeholders believed the crisis was over. Budget lines were trimmed. Suddenly, institutions that once had surplus capacity now face reactive pressure.

3. Logistical Complexities

SIT operations require coordinating aeronautical flights, centralized insect factories, and trained personnel. Scaling up or pivoting to new zones is far from plug-and-play.

4. Wildlife Vectors

Many wild animals can harbor larvae. Tracking and treating these hosts is far more complex than managing livestock. Ecosystem-wide surveillance is still underfunded.

5. Global Health Focus Elsewhere

In the COVID-19 and avian flu era, biosurveillance resources were diverted. Pathogens like screwworm, historically neglected, now enjoy less frontline attention.

The Path Forward

Combating the screwworm resurgence demands unity across agriculture, science, government, and diplomacy:

1. Optimizing Sterile Fly Production

The USDA investment in Mexico is timely. Once online, a surge to 160–200 million sterile insects weekly will reduce time lags and offer buffer strength.

2. Strengthening the Pan-American Corridor

Extending sterile-release barriers beyond Panama, ideally through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and southern Mexico, creates a “belt of biosecurity” that prevents mass reinvasion.

3. Fast-Track Diagnostic Expansion

Portable livestock wound-testing kits (e.g., LAMP assays), combined with local tissue-sample labs, cut red tape and detection latency. APHIS and Mexico must co-invest in shared diagnostic hubs.

4. Adaptive Laws & Emergency Funding

The STOP Screwworms Act should include automatic triggers; if screwworms are detected within a specified radius (e.g., 500 miles of U.S. border), federal emergency funds and SIT resources deploy immediately.

5. Grassroots Producer Training

Through extension networks and vet schools, cattlemen and independent ranchers near the border should receive free training in larval identification, wound management, and mandated reporting protocols.

6. Next-Gen Genetic Tools

Research consortia like the Joint Biosecurity Initiative should accelerate trials on gene drive-based suppression systems while testing for ecological safety.

7. Synchronized Cross-Border Surveillance

Weekly data-sharing between USDA and Mexico’s SENASICA (National Service for Health, Safety, and Agri-Food Quality), with border labs contributing real-time GIS maps of outbreaks and sterile-release zones.

What Producers Can Do Right Now

Even before federal responses reach full steam, cattle ranchers, feedlot operators, and smallholder farmers can take proactive defense steps:

- Regular Wound Inspections: Conduct daily body checks for fresh or slow-healing wounds—even minor abrasions can attract female screwworms.

- Prompt Veterinary Treatment: Open sores should be cleaned, treated with approved insecticides, and covered.

- Keep Good Records: Note any suspect cases, animal ID numbers, dates, and wound progression. These details can prove vital in an outbreak investigation.

- Restrict Movements: Keep new livestock quarantined and checked for at least 72 hours.

- Use Preventive Spray Programs: Approved dips or pour-on treatments reduce larval establishment.

- Stay Informed: Subscribe to local Extension alerts and monitor USDA/APLUS status bulletins.

When an Outbreak Strikes

Should screwworm larvae be confirmed?

1. Isolate the Animal immediately.

2. Apply prescribed larvicides and clean the wound thoroughly.

3. Report the case to your vet, state animal-health office, and the local USDA-APHIS regional office.

4. Follow containment protocols, which may include quarantines, animal movement restrictions, and SIT releases in your region.

5. Cooperate with authorities—they may conduct aerial sterile releases or impose movement controls temporarily. Compliance helps restore freedom faster.

A Collective Defense

Screwworms are more than just a “livestock problem”; they symbolize weaknesses in our collective disease defenses. Whether it’s animal or human health, pathogens remind us: prevention is far cheaper and more humane than a cure. In today’s interconnected globe, a multifaceted response is essential: sterile insect science, robust surveillance, sharp diagnostics, funding readiness, border cooperation, and frontline livestock vigilance.

That’s why Secretary Rollins is right to say, “This cannot happen again.” We don’t just risk billions in losses, but the very trust that consumers place in American meat, the resilience of rural livelihoods, and the future of coordinated global health response.

Looking Ahead

If action continues on its current trajectory, with increased production capacity, SIT releases expanding southward, and bipartisan legislative backup, the odds are good that screwworms will be stopped short of U.S. soil.

But history offers little room for complacency. Climate shifts, bureaucratic fatigue, and transboundary policy mismatches all pose stealthy challenges. Our best defense is constant vigilance, logistical resilience, scientific refinement, and agricultural community empowerment.

Ongoing investments in sterile-insect infrastructure, gene innovation, and education can help ensure that current screwworm alerts don’t spiral into a full-blown crisis.

We can, and must, be smarter this time. The lessons of the past, America’s thirty-year fight and resurgence, must become the backbone for a future where screwworms remain a relic of yesterday.