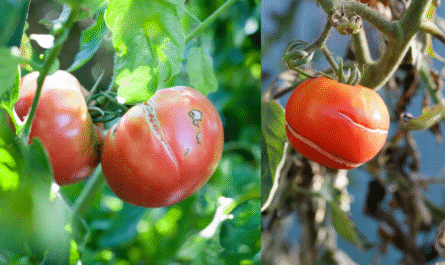

I’ve grown tomatoes for years, and I still get that sinking feeling every time I see black spots creeping across the leaves. It usually starts small, just a few specks on the lower foliage.

But if left unchecked, it spreads fast and can take out an entire plant before the fruit even ripens. If you’re seeing black spots on your tomato plants, don’t ignore them. They’re a warning sign, and understanding what’s going on is the first step to saving your crop.

These spots are more than just cosmetic. They usually point to disease, and if you don’t get ahead of it, the damage can be irreversible. I’ve battled everything from Septoria leaf spot to bacterial speck and even sunscald that mimics disease symptoms. And over time, I’ve learned how to identify the real cause, treat it effectively, and most importantly, prevent it from returning the next season.

In this post, I’ll walk you through what causes black spots on tomato plants, how to identify one of the most common culprits (Septoria leaf spot), and the methods I use to treat and prevent it. I’ll also share hard-earned lessons and practices that have helped me grow healthier, more resilient tomatoes year after year.

Common Causes of Black Spots on Tomato Plants

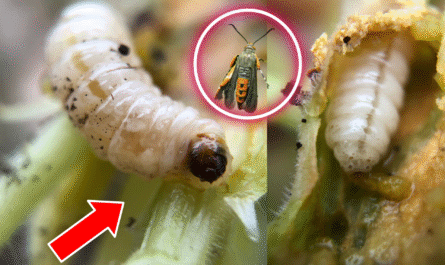

Tomato plants can develop black spots for several reasons, and not all of them are caused by the same pathogen. The most common culprit is Septoria leaf spot, but you’ve also got early blight, bacterial speck, bacterial spot, anthracnose, and even pest-related damage that might appear similar. The trick is knowing how to tell them apart, and that’s not always easy.

Sometimes, I’ll see gardeners jump straight to a chemical spray without diagnosing the issue first. That’s a mistake. For example, early blight causes larger spots with concentric rings and tends to affect both leaves and stems.

Bacterial speck shows up on fruit and younger leaves. Spider mites can leave behind tiny black fecal spots that look like disease. The right treatment depends on the correct ID, which means inspecting the plant closely and noting patterns, like whether the damage starts low on the plant or appears all over.

Environmental stress can also mimic disease. I’ve seen black spotting caused by overwatering, sunburn, or even fertilizer burn. That’s why context matters. Consider the recent weather, your watering habits, and whether your soil drains well. Sometimes what looks like a disease is actually a stress response, and misdiagnosing it could lead you to treat the wrong problem.

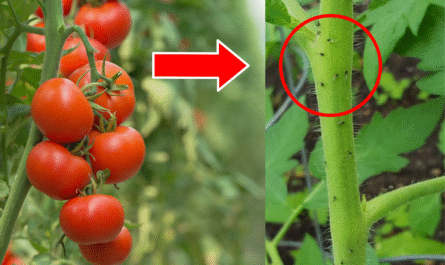

Identifying Septoria Leaf Spot

In my experience, Septoria leaf spot is the most common cause of black spots on tomato leaves, especially in humid regions or after a stretch of rainy weather. It typically starts on the lower leaves, with small, circular spots that have dark edges and a lighter gray or tan center. You might even see tiny black dots in the middle of each spot, which are fungal fruiting bodies. That’s a dead giveaway.

This disease spreads quickly in warm, wet conditions. Splashing water, whether from rain or overhead irrigation, moves the spores from the soil to the leaves and from leaf to leaf. I’ve noticed it tends to show up a few weeks after the first heatwave, when the canopy starts to get dense and airflow decreases. That’s when the perfect storm hits: moisture, warmth, and stagnant air.

What makes Septoria tricky is that the symptoms can look a lot like other diseases, especially early blight. But unlike early blight, Septoria doesn’t usually affect stems or fruit. It focuses on leaves, and once it starts, it doesn’t stop unless you intervene. The bottom leaves turn yellow and die off, and soon the plant is struggling to support fruit production. That’s why I act fast when I see those early signs.

Remove Infected Leaves

One of the first things I do when I spot Septoria is strip the infected leaves from the plant. It feels drastic, especially if the plant is already losing a lot of foliage, but it’s necessary. If you leave those leaves on, they’ll keep releasing spores and infecting new growth. I always start with the lower branches since that’s where the disease begins.

When removing leaves, I use sanitized shears and make sure not to touch healthy parts of the plant after handling infected ones. I’ve made that mistake before, accidentally spreading the spores by brushing against clean leaves. Now I clean my tools between every cut and never compost infected leaves. Instead, I bag them and toss them in the trash or burn them if local laws allow.

Even though removing foliage can stress the plant, it also opens up airflow, which helps dry out the remaining leaves and slows the spread. I’ve seen this simple step halt disease progression when caught early. It’s not a cure, but it buys you time, and time matters with fungal infections.

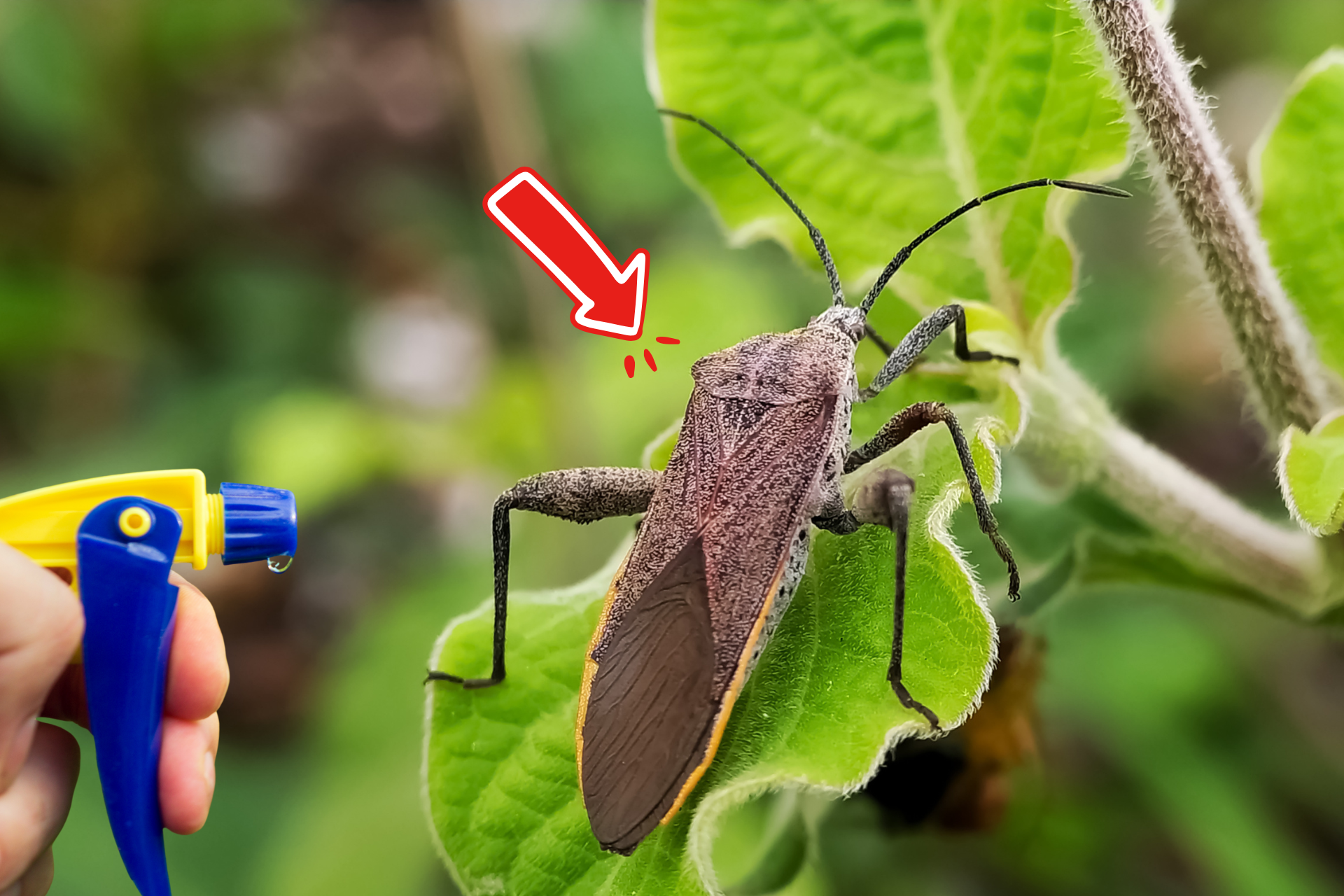

Try a DIY Spray

After removing infected leaves, I often turn to homemade remedies, especially if I catch the disease early or want to avoid chemicals. One of my go-to solutions is a baking soda spray. I mix 1 tablespoon of baking soda with 1 teaspoon of mild soap (like Castile) in a quart of water. This raises the pH on the leaf surface, making it harder for the fungus to thrive.

Another option I’ve used is diluted hydrogen peroxide, which has antimicrobial properties. I usually go with a 1:4 ratio of peroxide to water and apply it in the morning to prevent sunburn. Neem oil also works well, not just for fungi, but for pests too. The key with any of these sprays is consistency. One application won’t do much. I spray every 5–7 days, especially after rain.

That said, DIY sprays have limitations. They work best as preventatives or in very early stages. Once the disease takes hold, they can slow it down but not eliminate it. That’s why I never rely solely on them if the plant is already in trouble. Still, they’re a great tool to have in your arsenal, especially for organic gardeners.

Apply Chemical Treatments

If the disease is advanced or spreading fast, I don’t hesitate to bring out the fungicide. My go-to products include copper-based fungicides and those containing chlorothalonil. These are broad-spectrum treatments that knock down fungal pathogens quickly. I always follow label directions to the letter, especially when it comes to timing and reapplication intervals.

I alternate between products to prevent resistance. Fungal pathogens can adapt if you use the same chemical over and over. That’s why I rotate between copper and something like mancozeb. I also avoid spraying during the heat of the day. Early morning or late afternoon is best, it gives the spray time to dry without burning the leaves.

For those growing organically, OMRI-listed fungicides are available. I’ve had decent results with copper sulfate and Serenade (a bio-fungicide). The trade-off is that these often need more frequent applications. Either way, once you start treating chemically, you need to stay consistent for at least a few weeks until the plant stabilizes.

How to Prevent Septoria Leaf Spot

1. Choose Disease-Resistant Varieties

One of the smartest things I’ve done is switch to tomato varieties that are resistant to common diseases. Resistance doesn’t mean immunity, but it gives you a huge advantage. Varieties like ‘Iron Lady,’ ‘Defiant,’ and ‘Mountain Magic’ have shown strong resistance to Septoria and other foliar diseases in my garden.

When I’m selecting seeds or seedlings in early spring, I always look for codes like “SL” (Septoria Leaf spot), “EB” (Early Blight), or “F1/F2” (Fusarium resistance). These indicators help me stack the odds in my favor. It’s not foolproof, but I’ve noticed fewer outbreaks and better yields with resistant cultivars.

It’s worth noting that heirlooms are often more vulnerable. I still grow a few for flavor, but I manage them differently, with more spacing and preventive treatments. Mixing resistant hybrids with a few heirlooms has become my balanced approach to disease management.

2. Rotate Crops

Tomatoes and their relatives, peppers, eggplant, potatoes, shouldn’t grow in the same spot more than once every 2–3 years. Fungal spores like those from Septoria can overwinter in soil or on leftover debris. If you replant in the same place, you’re inviting trouble. I learned this the hard way after planting tomatoes in the same raised bed two years in a row and watching disease hit earlier each season.

Now I rotate with crops from different plant families, like beans, carrots, or leafy greens. If space is tight, I use grow bags or containers to break the cycle. Even moving your tomatoes 10 feet away can make a difference. The goal is to disrupt the pathogen’s lifecycle and give your plants a fresh start.

Adding cover crops or solarizing the soil during the off-season can also reduce disease pressure. These are long-term strategies, but they pay off over time, especially if you’ve dealt with repeated infections.

3. Avoid Overcrowding

Dense plantings trap moisture and block airflow, two conditions Septoria loves. I space my tomato plants at least 24–30 inches apart, more if they’re indeterminate and will grow tall. I also stake or cage them early to keep foliage off the ground and encourage vertical growth.

Pruning helps, too. I remove suckers and any lower leaves that start to yellow as the plant matures. This isn’t just about keeping things tidy, it reduces humidity around the plant and makes it harder for fungal spores to spread. I prune weekly during peak season and adjust based on weather.

Every time I’ve tried to squeeze in “just one more plant,” I’ve regretted it. Overcrowding always leads to more disease, more maintenance, and fewer tomatoes. Give your plants room to breathe, they’ll reward you with better health and higher yields.

Final Thought

Black spots on tomato leaves aren’t just an aesthetic issue, they’re a red flag. I’ve learned to treat them seriously and act quickly. Whether it’s Septoria leaf spot or something else, early action can save your harvest and your sanity. I don’t wait and hope it’ll go away, it won’t.

Over the years, I’ve developed a toolbox of strategies, from simple pruning to advanced rotation planning. None of them are one-size-fits-all, but together, they make a huge difference. Gardening isn’t about perfection; it’s about staying observant, making adjustments, and learning from every season.

If you’re dealing with black spots, don’t panic. Take it one step at a time: diagnose, treat, and prevent. You’ll get better results with every season, and before long, those once-troubled plants will be cranking out flawless fruit.

FAQs

Septoria spores can survive in soil or plant debris for up to 2–3 years. That’s why crop rotation and cleanup are so important for long-term management. No. Fungal diseases like Septoria won’t resolve without intervention. They will continue to spread until conditions are no longer favorable or the plant dies. To a degree. Certain plants like basil or marigold may help deter pests, but they won’t stop fungal diseases outright. Companion planting works best as part of a broader strategy. It depends. If the plant still has healthy growth and is producing fruit, it’s worth trying to save. But if 70% or more of the foliage is affected, sometimes it’s better to remove it to protect nearby plants. How long does Septoria stay in the soil?

Will black spots go away on their own?

Can companion planting help reduce disease?

Is it worth saving a heavily infected plant?